I was invited to take part in an Editors’ Forum in ASAP/Journal on the question of “What is a Question?” The prompt invited artists and scholars to use their own work to describe how they formulate critical problems: “What does it mean to pose a question—and to whom and to what ends are such questions posed?” Here is my response about Breath Catalogue specifically and inquiry in artistic research more generally:

I often teach a two-term graduate-level methods class on practice-as-research. The pedagogical framework is designed to guide students through the process of generating performance by gradually accumulating a constellation of questions. The first term uses a “devise and shed” format to model what it means to follow a line of inquiry. Each week students present material to be discussed by their peers; their task for the following week is to let go of everything they had previously done and begin again, retaining only the part of their work that had emerged as the most sticky in discussion. This “stickiness” can encompass many types of critical thresholds: a friction, for instance, between the ideas that students are grappling with and the artistic process or even medium through which they are trying to do so. This leads to a question or set of questions that becomes the catalyst for a new practice, which is then performed the following week, with the same follow-up task, and so on. It is only during the second term of the course that students are allowed to hold on to their working questions; this ultimately builds to a single performance in which those questions materialize in new forms.

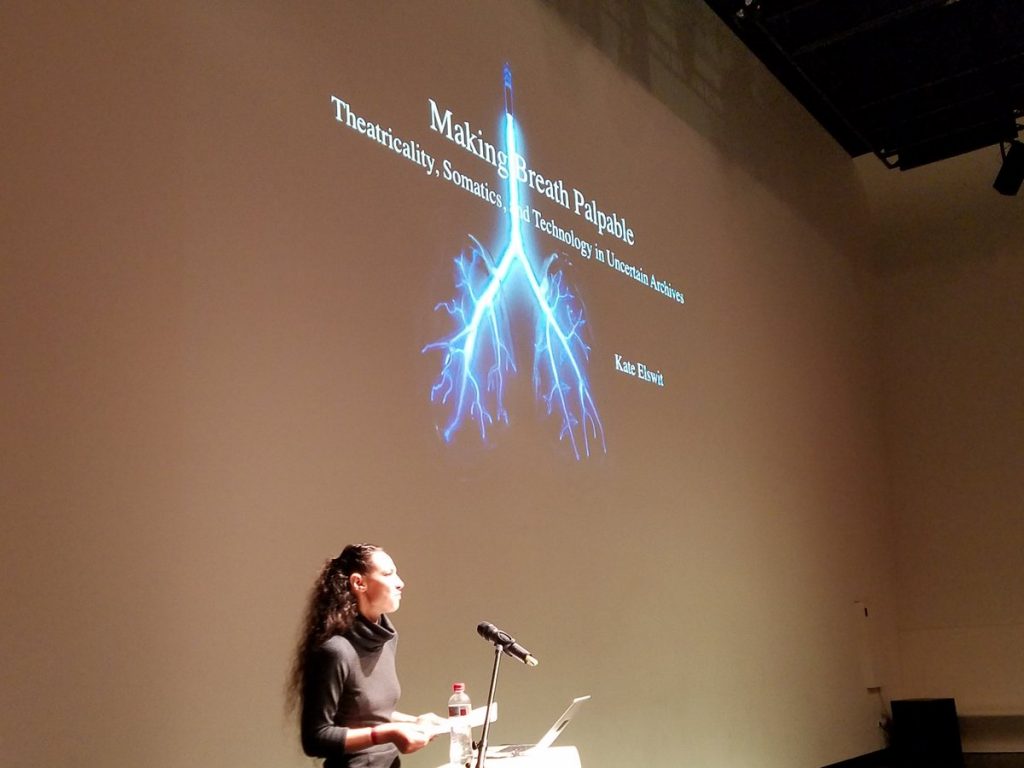

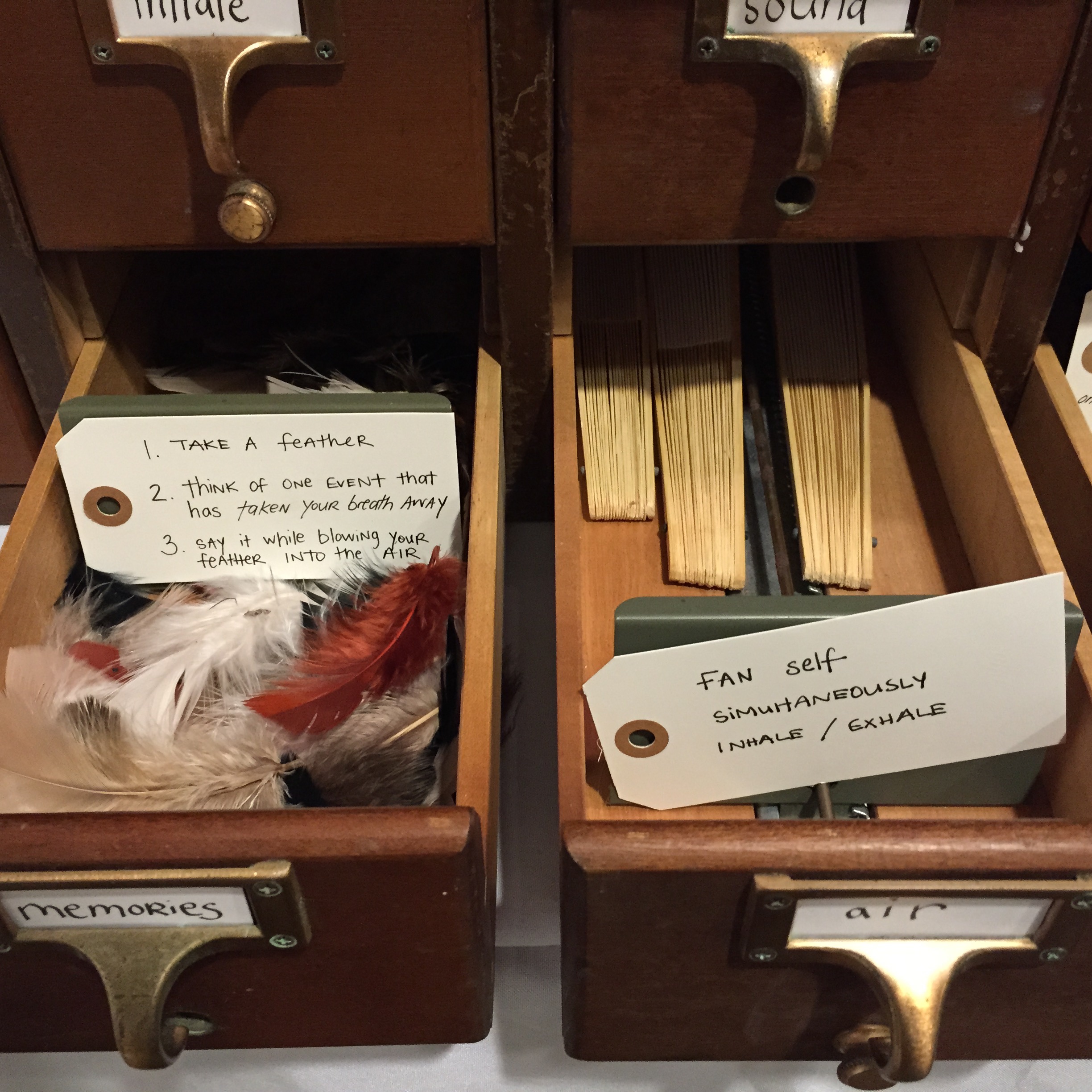

In my own work Breath Catalogue, such a constellation of questions emerges from multiple strands of inquiry that have to do with embodiment, theatricality, technology, and medicine. The often provisional sub-questions of each strand that have been most generative for my collaborators and me articulate concerns arising in the rehearsal studio, while also facilitating discovery through the conditions they pose for possible action. To give a quick background, this research project combines contemporary choreography with technology to create a cabinet of “breath curiosities” in performance. I collaborate with another artist/scholar, Megan Nicely, as well as data scientist and interaction designer Ben Gimpert, and composer Daniel Thomas Davis. Taking inspiration from the old European cabinet of curiosities, we collect, save, and re use breath experiences and breath data. This ranges from the stories people tell us or our own choreographies of breathing, to the interaction in performance with additive visualizations that mix the dancer’s live breath from one scene with archived breath from the previous one. The cabinet and indeed the curiosity or curious thing become ways to assemble questions within an artistic framework.

The first strand of inquiry for Breath Catalogue involves questions about embodiment, both everyday and dancerly, that are posed as starting points for physical practice. From the beginning, we have been interested in complicating the intrinsic connections between breath and movement in dance, in order to access forms of breath that circulate independently of a single body. So what happens when, instead of relying on breath to support solo movement patterns, we ask breath and body to move autonomously, and what cues do we need to actually do so? Likewise, instead of breath being the “felt” thing that connects two dancers, can it be visualized as an external third component in the relationship, and what might this catalyze?

This leads to questions about sharing such forms of bodily experience with others through a theatrical medium: how do we bridge the gap between the visual or sonic representations of breath, and the somatic experience of breathing, in order to make the many dimensions of breathing palpable to an audience? Whereas in a “normal” dance show, the breath would tend to be obscured behind lots of movement, we ask whether there are ways to shift that hierarchy in order to keep the breath as a priority for spectators watching a moving body that has all sorts of other things going on.

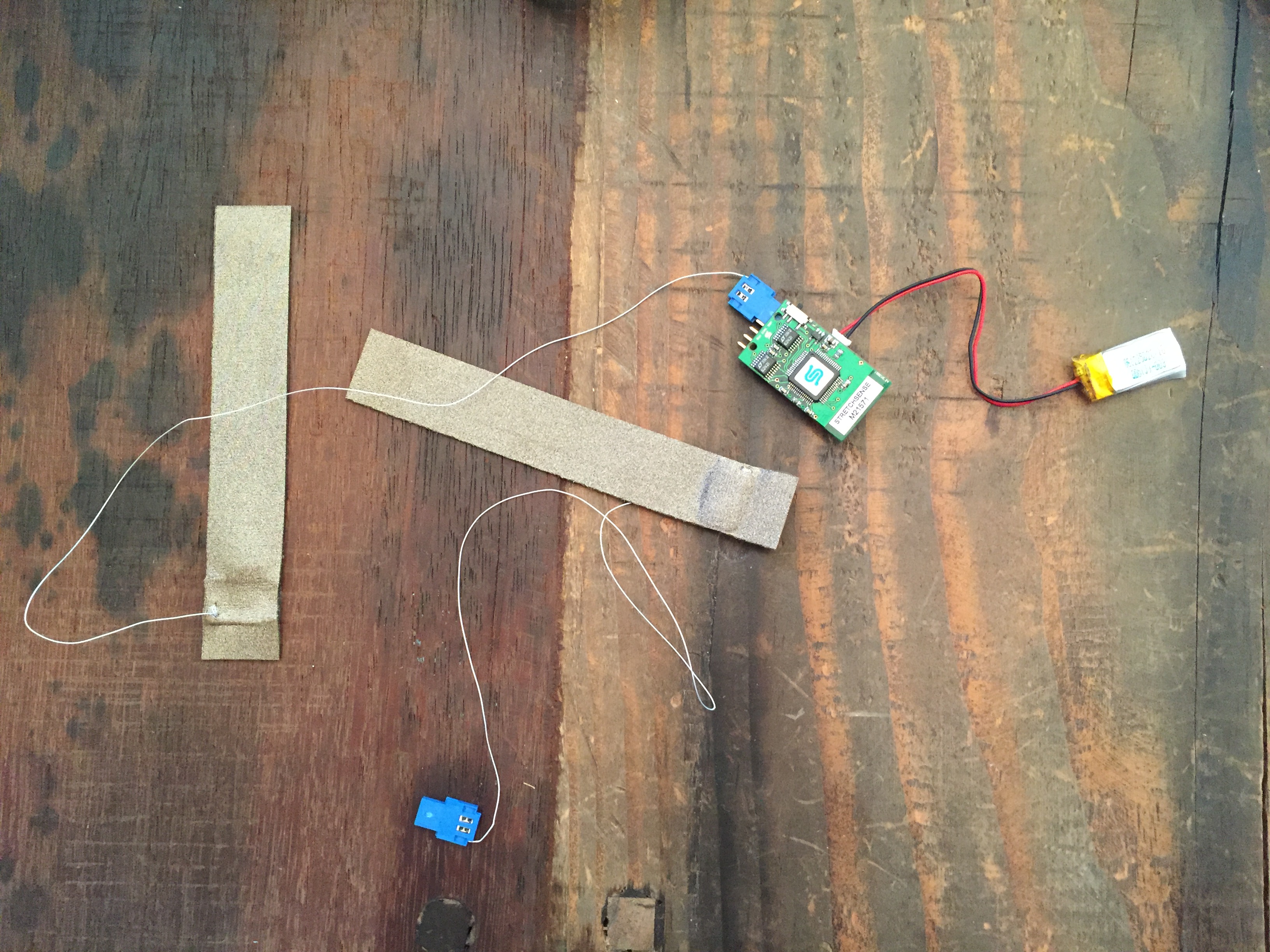

Using wearable technology to pursue these strands of inquiry also raises other sets of questions. First there are practical issues: for example, because our sensors cannot intrinsically distinguish the movement of breath from other forms of movement that expand the chest, what ways of moving allow the sensors to register breath? The technology has the potential to make breathing visible in a way that is otherwise impossible for the dancing body alone, but there is also a massive difference between an expert dancer’s experiences of breath and what a monitor can pick up and quantify. In what ways can these two forms of expertise inform one another? There are also cultural implications of breath in this context: in this moment of the increasingly quantified self, when wearable personal sensor technology is currently being sold to consumers as a way to buy mindfulness, happiness, and health, many technologies of the quantified self tend to treat the body as an object to be disciplined rather than expanding corporeal registers of feeling. So how can dance help to model a more curious approach to the quantified self that builds new somatic and artistic feedback loops?

A newer strand of inquiry involves the medical aspects of Breath Catalogue. The nature of this project, through which we experiment in making our breath palpable to others, sometimes results in audiences wanting to share their breath experiences with us, often in the context of respiratory illness and other non-normative breathing patterns. During an artistic residency at Southmead Hospital, I discovered the answer to the why-question I had not yet asked: namely, that many of the exercises we devised choreographically by inserting spaces between breath, movement, and speech actually map onto pathological symptoms—for example, the “speaking in broken sentences” that is used to diagnose clinical breathlessness. Whereas Breath Catalogue began from an investigation into our own breathing, we are now grappling with how we can not only take the breath patterns of others into our own catalogue, but also allow them to inform what we retrieve for future performances. Many audience members describe holding their breath with us at times. So how can we push the breath in a way that is—at minimum—safe for, and perhaps even useful to, those with respiratory illnesses? And given that medical professionals and patients struggle with the unsharability of breath experiences, can our work help them in some fashion?

The devise-and-shed format of my methods course models how such individual strands of inquiry can be developed. By attending to the students’ critical thresholds, it ultimately builds toward constellations of questions as they proliferate, layer, and interweave. With Breath Catalogue, this can be understood in terms of the curios in a cabinet of curiosities, as well as the attitude of inquisitiveness that accompanies such critical and affective collection without necessarily seeking solutions. The historical form of the cabinet comes from a moment when the distinctions between scientific and artistic experiment were less defined than they are today. I am interested in how recalling the curious practice of accumulating and organizing, whether things or indeed questions, may be useful today to considering bodies differently.

Kate Elswit “What is a Question?” ASAP/Journal, 2.1 (2017), 34-36